Portfolio Manager Insights | Using Behavioral Finance to Set Investor Expectations — 1.14.26

The strong stock market performance of the past several years has been positive for investors and their financial plans. At the same time, these recent successes can lead to unrealistic expectations when it comes to long-term financial goals. This is because investing and financial planning occur through all parts of the cycle, in both good and bad markets. So, while benefiting from investment opportunities and managing risk are important, it’s just as critical to set proper expectations grounded in history, analysis, and tailored financial plans.

The field that studies human reactions when it comes to investing is known as behavioral finance. Over 50 years of research tells us that people can be prone to both cognitive and emotional biases that often lead to suboptimal outcomes. Most investors understand that we cannot directly control how markets will behave, how the economy will perform, or what policymakers will do in Washington. However, we can control our own behavior in response to events and headlines.

Understanding these biases is not an academic exercise but a practical skill set for making better decisions. The reality is that we all face behavioral biases, which have little to do with our intelligence or educational backgrounds. What separates successful long-term investors is not the ability to eliminate these biases entirely, but rather following systems and frameworks that ensure we make productive decisions in spite of them.

Focus on the big picture and not just recent events

First, it’s natural for investors to base their investment decisions on recent events, since these are front and center in the news. This concept is often known as recency bias, which can be a problem if too much weight is given to recent events at the expense of long-established facts. In other words, it’s the idea that “this time is different” based on only a few data points.

After the S&P 500 experienced double-digit returns in six of the past seven years, it’s natural for investors to begin viewing this as normal rather than exceptional. This can lead to two problematic outcomes: either expecting the trend to continue indefinitely or believing that a correction is “overdue” simply because markets have performed well.

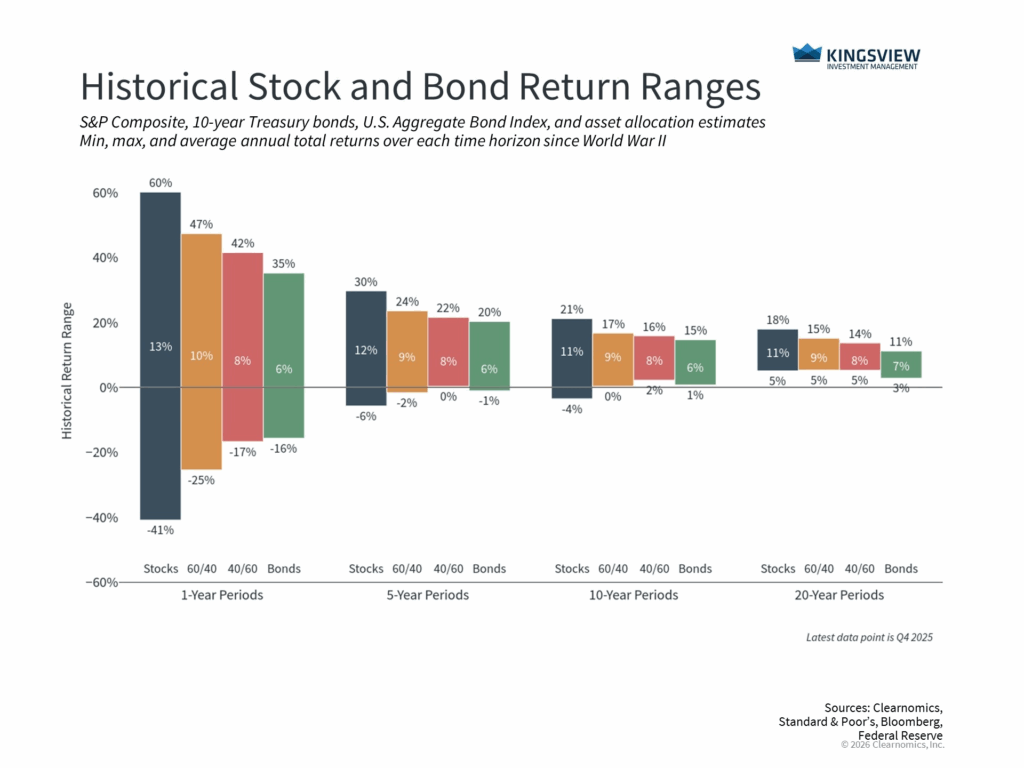

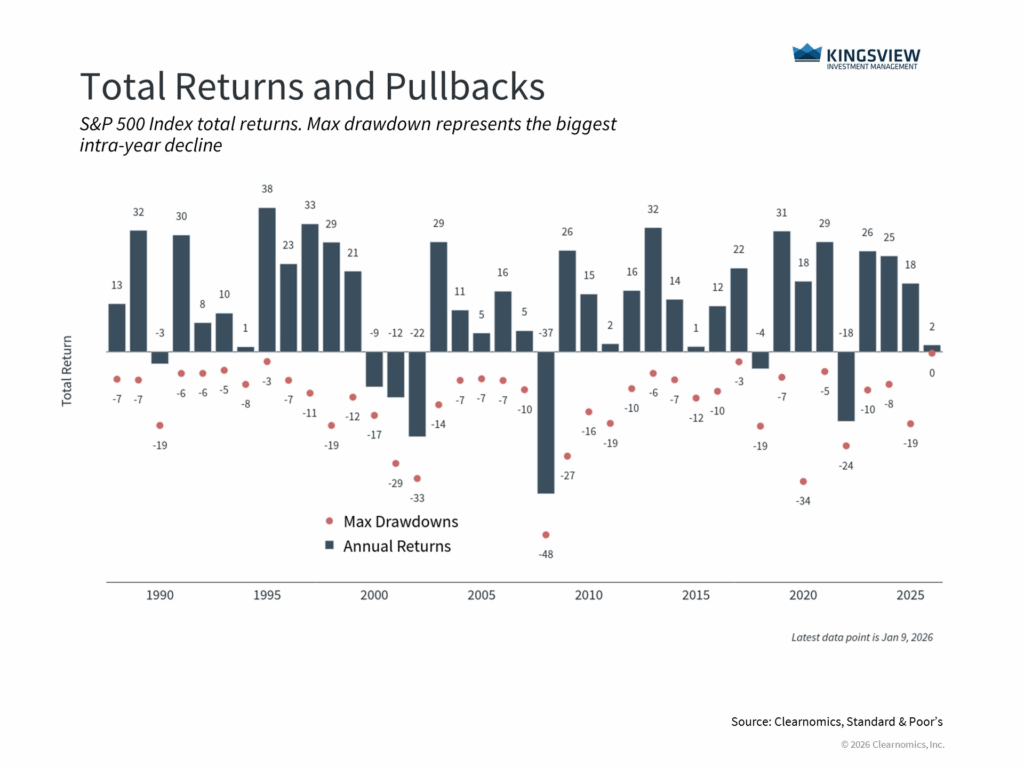

History tells us that the situation is more nuanced. The accompanying chart shows that while the S&P 500 has experienced an average annual total return of more than 10% over the long run, individual years can vary dramatically. The recent string of strong years isn’t unprecedented in market history, but it also doesn’t guarantee future results. Rather than trying to predict what will happen in a given year based just on the past few years, long-term investing is about taking advantage of this overall positive pattern.

What makes recency bias especially challenging today is how it interacts with another bias known as “herd mentality.” When markets are rising, the fear of missing out can drive investors to abandon their carefully constructed plans. They may increase stock market allocations beyond appropriate levels, chase growth sectors like artificial intelligence and technology, or take on unnecessary risk. History shows that investor sentiment comes and goes, so what’s important is to not get caught up in any individual wave.

The solution to these biases isn’t to ignore recent performance, but to view it within proper historical context. Strong returns are positive and should prompt portfolio reviews to ensure that asset allocations are still aligned with long-term goals.

View gains and losses objectively, not emotionally

Another bias that is relevant today is the idea that investors don’t experience investment gains and losses in an objective way. The long history of the stock market makes this clear. When viewing the S&P 500 over decades, for instance, stock market downturns occur occasionally but are less significant than the long-term trajectory of the market. Yet in the moment, these declines can trigger strong emotional responses.

Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, two psychologists whose research forms the foundation of behavioral science, wrote that “losses loom larger than gains.” This describes a concept known as loss aversion, or the tendency for individuals to feel the pain of losses more intensely than the joy of similar gains. For instance, imagine winning $100 and the excitement that might bring. Now, compare that to losing $100 of your hard-earned money and how that might affect your day. For many, the feeling of loss is what stays with them and drives future decisions.

This matters because achieving financial goals requires staying invested and disciplined through ups and downs. The chart above shows that even though the stock market has risen in two-thirds of years, it often experiences significant pullbacks during the year. Last year’s tariff-driven volatility is the perfect example. Those who exited markets too soon, or near the market bottom, would have missed the subsequent rebound which drove markets to new all-time highs.

Consider opportunities across asset classes, styles, sectors, and geographies

In today’s market, the concept of home bias, or the idea that investors tend to invest in what they know based on where they live, has grown in importance. One variation of this, known as home country bias, is the tendency to overweight domestic investments even when other regions may be attractive.

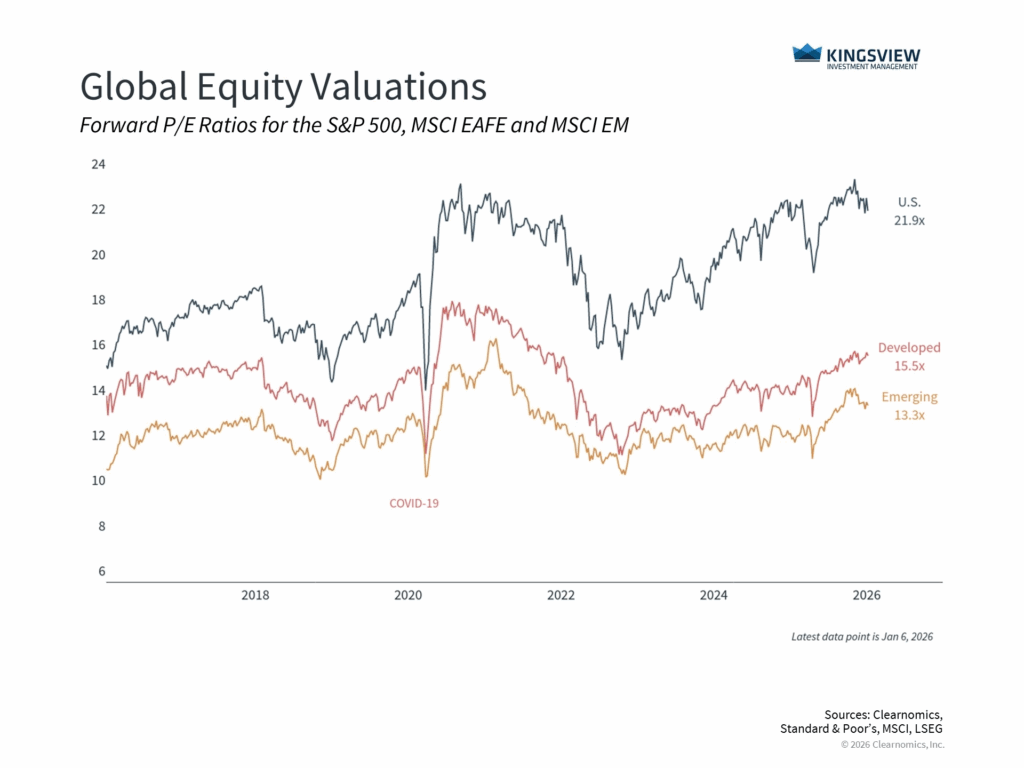

Over the past decade, U.S. stocks have indeed delivered strong returns compared to developed and emerging markets, driven by technology sector dominance and strong corporate profitability. However, this is not always the case. In 2025, the MSCI EAFE index of developed market stocks and the MSCI EM index of emerging market stocks both outperformed the U.S. in dollar terms. While there is no guarantee this pattern will continue, it highlights the importance of investing across asset classes and geographies.

History shows that market leadership changes over time and is difficult to predict. As the chart above highlights, international markets currently trade at lower valuations than U.S. stocks, and thus can help improve the risk-reward characteristics of portfolios. Ultimately, investing isn’t about maximizing returns in any single period, but about creating more consistent outcomes over full market cycles.

The bottom line? After several years of strong market performance, it’s important for investors to maintain proper expectations. History shows that the stock market has supported long-term portfolio growth, but this requires investors to control emotional responses to short-term events.